Fusion Days

I recently came across this article on the BBC website commemorating the end of Fusion experiments at JET fusion laboratory

This hit me hard, since it was only a mere 40 years ago, that I, a fresh-faced Physics student, entered the gatehouse at Culham, Oxfordshire to undertake my one and only contribution to British science as I started a 6-month placement at Culham Fusion laboratories.

In truth, it was an exciting time. When I was in the last year of A-levels, me and a few others on the Physics course at Sutton Coldfield College of Further Education had arranged a tour of the site. To be honest, I remember little of it now, but something must have stuck, and while fellow students at Sheffield Polytechnic were going to placements at such dry board manufacturers (where really they were used as cheap labour) I felt I was doing what I really wanted. Real cutting edge physics that would shape the future. My first step to the Nobel Prize would start here....

The truth was a little more prosaic.

The Culham site, was situated in leafy fields just outside Abingdon, consisted of not one, but two organizations.

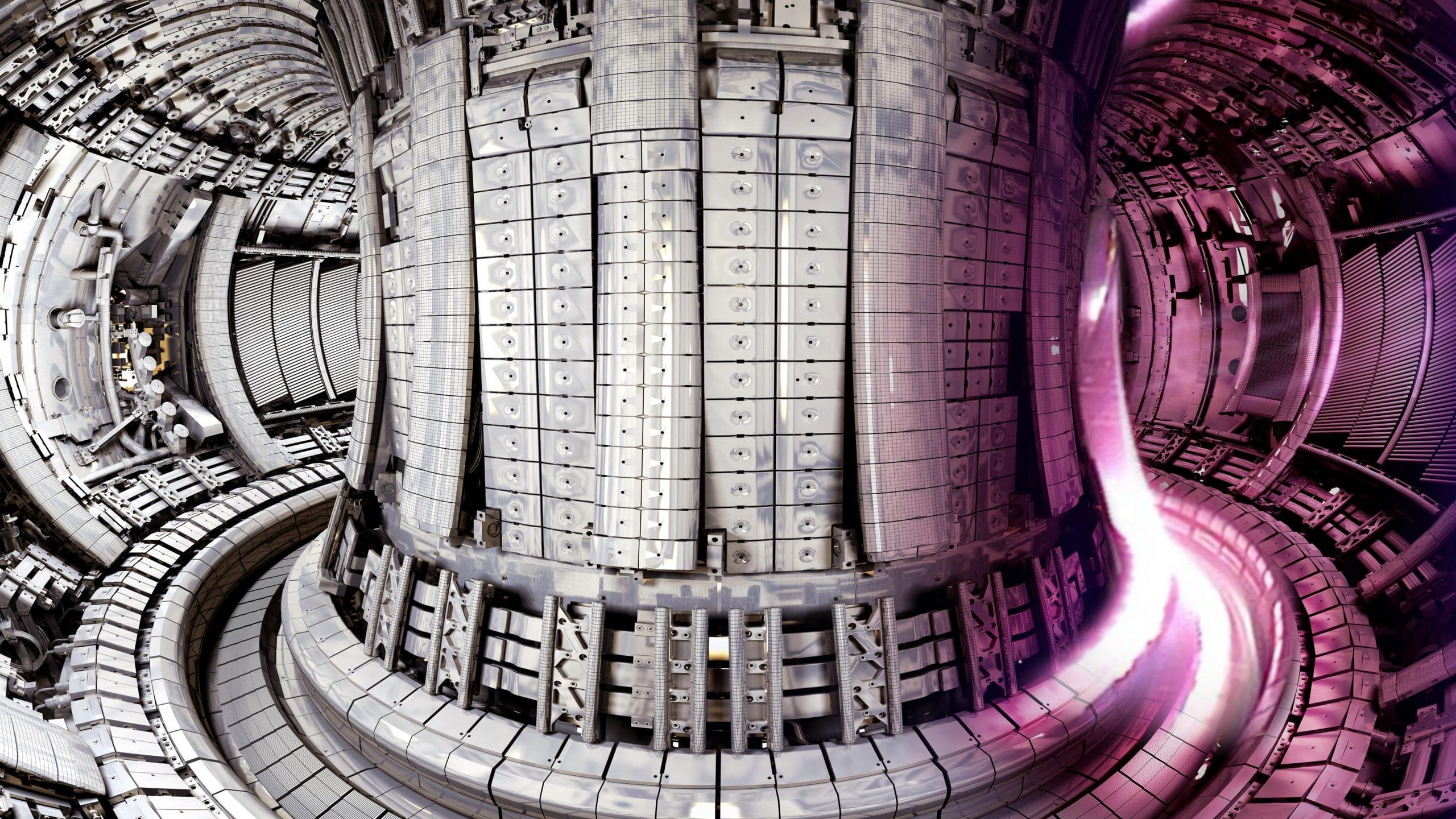

JET or the Joint European Torus, was a multinational laboratory bringing the best brains in European fusion research onto one site in an effort to bring to fruition the promise of limitless energy by joining hydrogen to helium. It was based in a gleaming glass building, accessed via a transparent archway bridge. It was new, impressive, and was for many years the cutting edge of nuclear technology, still holding the record for a sustained fusion reaction.

However, that was not to be my home. I was based in the UK fusion labs. Unlike JET, this was based in old buildings dating back to the 40's or earlier. It consisted ofa ramshackle collection of sheds and offices which was less designed and more evolved into some form of amorphous shape plonked onto the Oxfordshire plains.

While on the same site, and performing the same function, there was little interaction between each area. While both were aware of their existence, each kept to their own side (apart from in the cafeteria where each would mingle). In the 6 months I was there, I only went into the JET side once to ask for some postcards. The famed JET torus, and the rest, was always off limits for me.

The UK side was more accessible. My "office" for the want of a better word was an old wooden desk in a storage room, where the accumulated junk of many years had been dumped. I spent many a happy hour, delving through old wooden boxes, to see what treasures lay in them. Generally they consisted of old pressure sensors and various pieces of metal of unknown origin. Nor was this unique. You would often wander around and find buildings with old forgotten stores, like they had abandoned like some Saxon hoard, to be recovered, but the original owner never returning.

As well as store rooms, there were other areas of treasure for a young 20 year old. At a time before the first PC's were available, there were rows of PDP-11's mini-computers together with the racks of giant disks that you plugged into the top with a satisfying clunk. These were used to control experiments, gather data and do calculations. While less power than my present mobile phone, they were a great tool to practice programming on, and I would often play around with them generating waveforms on crude CRT displays attached to them.

And of course there were the experiments. Unlike the JET site whose purpose to drive Fusion physics to its final form, the Culham site purpose was more to explore the edge cases of other approaches. There were a number of experimental models, but unlike the JET pristine engineering, these were more put together with string and gaffer tape.

The experiment I was associated was called Reverse Field Pinch. The idea being, as much as I could understand it, was a form of magnetic containment that would take less power to achieve the plasma densities required. In order to simulate it, I had a large fibreglass model of a tokamak where we could put low voltage fields through and measure the results. Of course now, you could probably simulate the entire thing on a raspberry pi using Mathcad, but the days of cheap computing power were some way ahead, and instead I had built my 1st electronic circuit running multiple 555 timers to try and simulate the plasma field, while the results could be picked off by two coils attached to oscilloscopes. I was very proud of the electronics, but today would look terrible primative.

One thing I do remember were the rooms with rows of capacitors required to drive the high voltage to generate the plasma required. While I was there, one which consisted of jars of castor oil, exploded with obvious fun results. In fact, one of the offshoots of the Culham work was to use the excess high voltage capacity to simulate lightening strikes on aircraft.

If Culham buildings had character, so did those who worked there. Some had looked like extra's from a 1940's documentary about Radar development wandering around in beige lab coats wuth glasses stuck to their forehead, others were characters in their own right. My supervisor, Paul Noonan, when he wasn't working on nuclear fusion, spent his time supporting the campaign for nuclear disarmament, by travelling down to Greenham common in his Hillman Avenger estate to protest the installation of US cruise missiles. His argument was that by developing Nuclear fusion, it would remove the need for Fission reactors and remove the primary source of enriched uranium.

Also, like so many places, they depended on a steady stream of interns and students. I fell into a group who lived in Oxford and often went up there for drinks and evening out, and it is a city I still love to this day. However, mixing with them I became painfully aware of my Academic inadequacies. Most of them were sourced directly from Oxford universities, and had skills and cultural awareness that far outstripped my more humble education. However, for a while I enjoyed being in their glow as we went to the local student cinema's, and then went back to crumbling student house for vast vegetarian stews while I listened to the latest chats picked up at the latest Oxford Union debates. I am sure I was a pain to Carl, Ash, and Steve Gee, but I didn't care since I enjoyed the Bohemian lifestyle of an Oxford Student.

Then there was Rush Common House. One of the great advantages of working a Culham in those days was the presence of a huge boarding house which provided accommodation for people working not only at Culham, but also the nearby Harwell and Rutherford Appleton laboratories. As such was a melting pot of people of all ages who would be bussed to their destinations in the mornings. The main advantage is that as a student surviving on the wages provided, there was no need to find accommodation in a City even then expensive to rent. It wasn't just students however, some people in their 50's and 60's seemed to be permanent residents and I often wondered about their backstory how they ended up there.

Much later in my life, I was travelling with a colleague from Manchester to Farnborough and they said they knew a great pub on the way in Abingdon. As I sat eating I had a feeling I had been there before, and I then realized that I was in the same pub just outside Rush Common House that I had been to many times before. So I asked if we could just go around the corner, only to find that Rush common House had now been torn down to become another housing estate.

The end

With many life memories, it is hard to put them in a strict chronological order, never mind provide an exact date. However I know exactly when my Culham experience ended. I had spent the morning packing my suitcases to get the train home to my parents, then I remember going to the packed TV room to watch the start of the Live aid event on Saturday 13 July 1985. I only had enough time to take in Status Quo and Ultravox before getting my train, so missing Queen, Bowie, but getting home in time to time to catch McCartney play "Hey Jude". It seemed a fitting swan song.

I was 21, the placement was the completion of my Physics course, and now I had to decide what my future would be. Although I did not know it at the time, my time at Culham helped me do that.

I came away knowing that despite my Physics qualification, I did not want to work in Physics.

At Culham, there were too many people who were so much more capable and brighter than me, but were working on pitiful wages. The British capacity to undervalue science and the scientist, compared to say finance services, was writ large there. If people with Oxford PHD's were living on such wages, what hope had I got? I was painfully aware (and don't laugh, kids) of my £200 overdraft and the need not to be a burden on my parents. However, Culham also gave me the opportunity to get confidence in my ability with computers, which channelled me into my career of the last 40 years.

My one regret is that I hoped to tell my kids that once I played a small part in solving the world energy crisis by developing clear, sustainable, safe fusion energy. Of course that would be a total lie, but it would have been good to of at least said I walked with giants.

When I went to Culham, commercial fusion only seemed 10 years away. Now, 40 years later, it still seems 10 years away Worse, the UK after its Brexit madness, threw away years of work with EURATOM and now will no longer be part of JET's replacement, ITER, instead deciding to go it alone and build its own commercial reactor. One of my takeaways from Culham is that the days of British exceptionalism in large science are long gone, and we work best when in partnership. The people who worked at Culham were talented, dedicated and driven. However, they were also served poorly by a UK government that has never really understood how science and innovation happens.

At Culham, they could at least ride the coat tails of JET. It is a pity the rest of country could not learn that we are better off when we work together.

As to the people I worked with, Paul Noonan went onto work in super conducting magnets and cryo-geneics and Steve Gee still works at Culham. As to the rest, they are only images without surnames.

However when I look back at my working life, despite all I have done and acheived, that brief 6 months spent stalking those Oxfordshire halls, are still the ones that bring me the most pleasure.

Comments

Post a Comment